Nearly 50 years after its release, Chantal Akerman's magnus opus has just been voted the best film of all time by Sight and Sound's prestigious film poll.

1:15am, December 3, 2022

On a quiet afternoon in April this year, I set aside three hours to watch Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Brussels, and it turned out to be some of the most eye-opening three hours of my life. I quickly realized I was watching a deeply rebellious film.

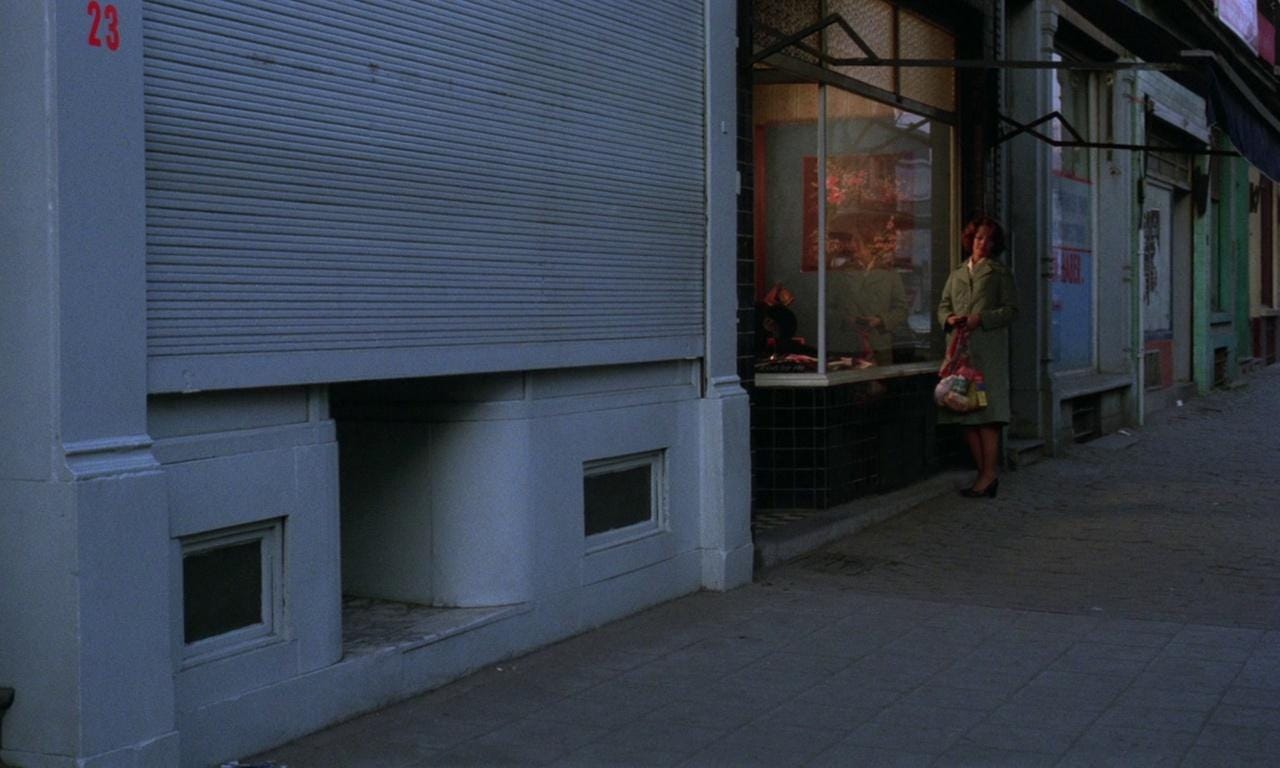

A static camera —which Yasujiro Ozu would love— peels back the highly regimented and routined life of Jeanne Dielman (Delphine Seyrig), a middle-aged widow, over the course of three days. In the morning she prepares her teenage son for school, carries out monotonous household chores; peels potatoes, cleans the kitchen, meticulously sets the dinner table, unfailingly saves money in a little ceramic pot, and has sex with different men to support her income.

This is a film only interested in showing you unadorned facts. It goes to the dark underbelly of existence: that most of our lives are moments of mundanity in which we're tied slavishly to our habits. Jeanne Dielman forces the memory into recollecting those seconds, minutes and days in-between pivotal events. Days like domestic dogs, static, bored, and repetitive. This is the blessing and curse of the film. Whenever I come across someone who doesn't like this seminal work of Chantal Akerman, their argument usually centers around the fact that life is boring and dreary enough, so why watch the exact same thing in a movie?

This raises the question, “should cinema then exist only as a tool to compensate for, and as an escape from, the repetitive cycle of life?”. I don't think so. The beautiful thing about watching Jeanne Dielman, for me, is that it served as a mirror, coaxing me to see, not just merely look, and appreciate the little things, because they set the stage for the explosive events of life. Though the film accomplishes this through a woman’s story, it's impact defies gender barriers.

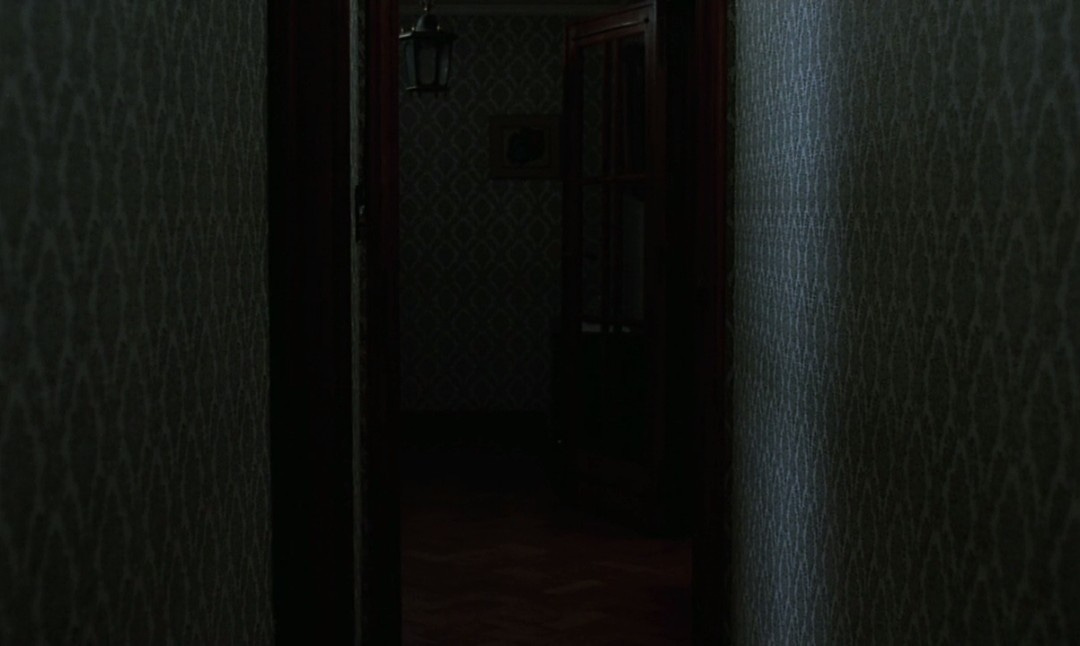

In an early scene, brilliant in its subtlety, Jeanne walks into the hall and, just outside the camera frame, greets another client for the day. As both of them disappear into Jeanne's bedroom to do business and shut the door, the camera stares at the closed door for a long time, like a well-behaved, domestic dog. I could almost hear Akerman say, “it is what it is, we all do what we must to make ends meet.”, but having seen Je, Tu, Il, Elle before, I sensed that she couldn't quite explain the scene in that way. To try to explain Jeanne's actions as portrayed in the film would be condescendingly reductive.

What is crucial is that we closely observe Jeanne to the point that when her routine is eventually interrupted, it took on the emotional force of a tragic event. In the unusually burnt potatoes, in her dishevelled hair which, hitherto, was always fastidiously kept, in her uncharacteristic failure to keep to time, etc., Jeanne's life unravels ominously. Because hers is a life held together by habits — She never leaves a room without switching off the light. She bathes herself in exactly the same way every morning and shines her son's shoes in the very same order. And like Jeanne, when our habits are interrupted, we implode. Perhaps this is what fuels Jeanne Dielman's critics —an aversion to seeing the truth of life's insipidity on screen.

For those who welcome the opportunity to face themselves in the mirror, Jeanne Dielman is a film in the mould of Richard Linklater's Boyhood, Arie & Chuko Esiri's Eyimofe and Lemohang Mosese's This Is Not A Burial, It's A Resurrection. They remind us to be introspective and empathetic. They remind us that, although we’re unique, we aren’t special. Its lengthy running time, just like its tragic ending, is also necessary, even though it takes something away from the full impact of its message. Jeanne Dielman wouldn't top my list of favorite films but it would stand heads and shoulders with most of them.

Rating — 9.

0 Comments

Post a Comment