A dialogue on sex on romance

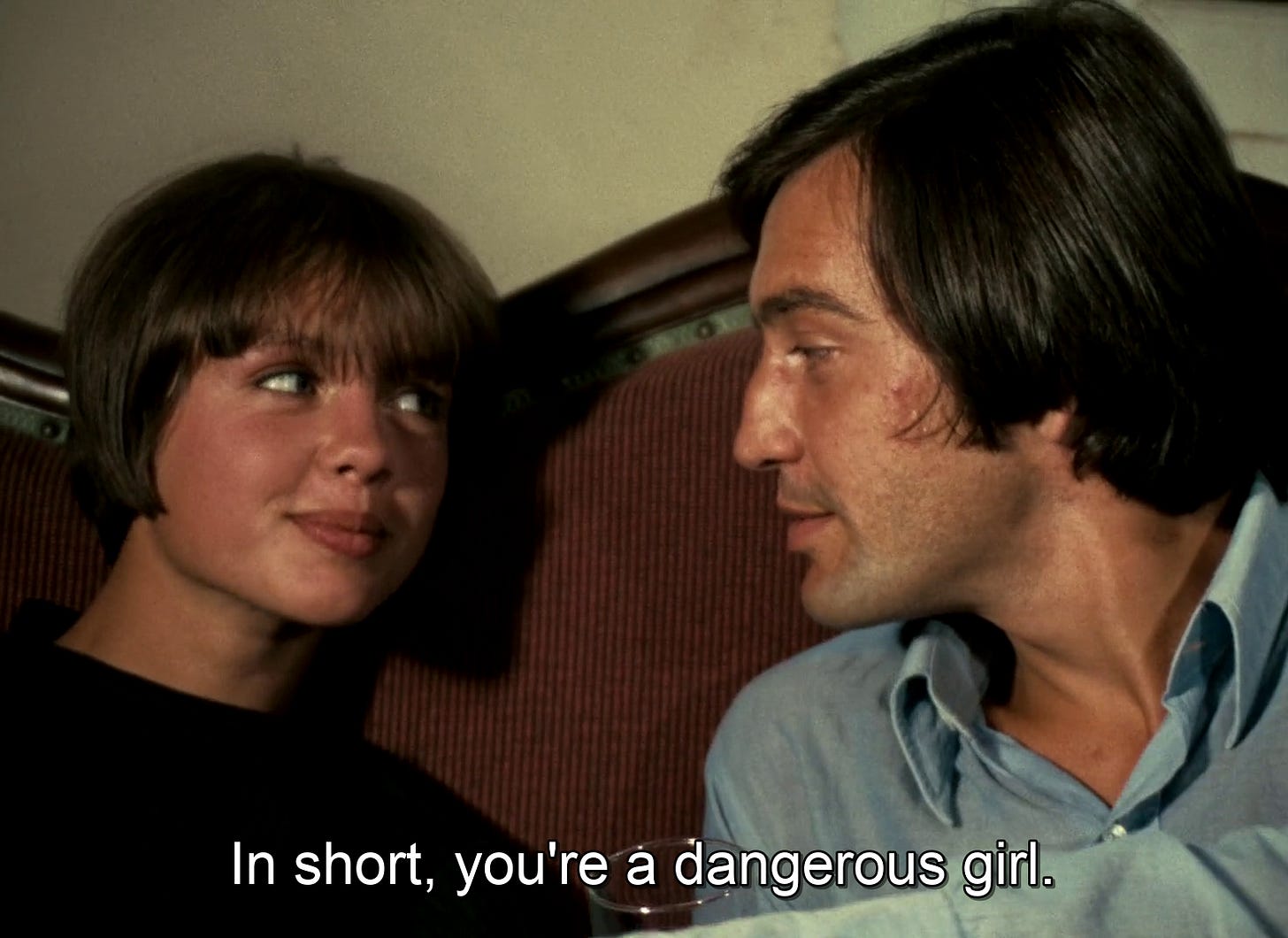

“LA COLLECTIONNEUSE,” — The Collector —, is Haydée (Haydée Politoff), a young woman holidaying at a villa near St. Tropez. Sharing the villa with her are Adrien, (Patrick Bauchau) who is convinced she’s a collector of men, and Adrien’s friend, Daniel (Daniel Pommereulle), a nondescript man who thinks Haydee is beneath him physically and intellectually. The two friends are about ten years older than Haydee, but once the brief prologues go by and inner motives are revealed in monologues and dialogue, it becomes clear that the men find it impossible to intimidate her and are in fact, intimidated by her.

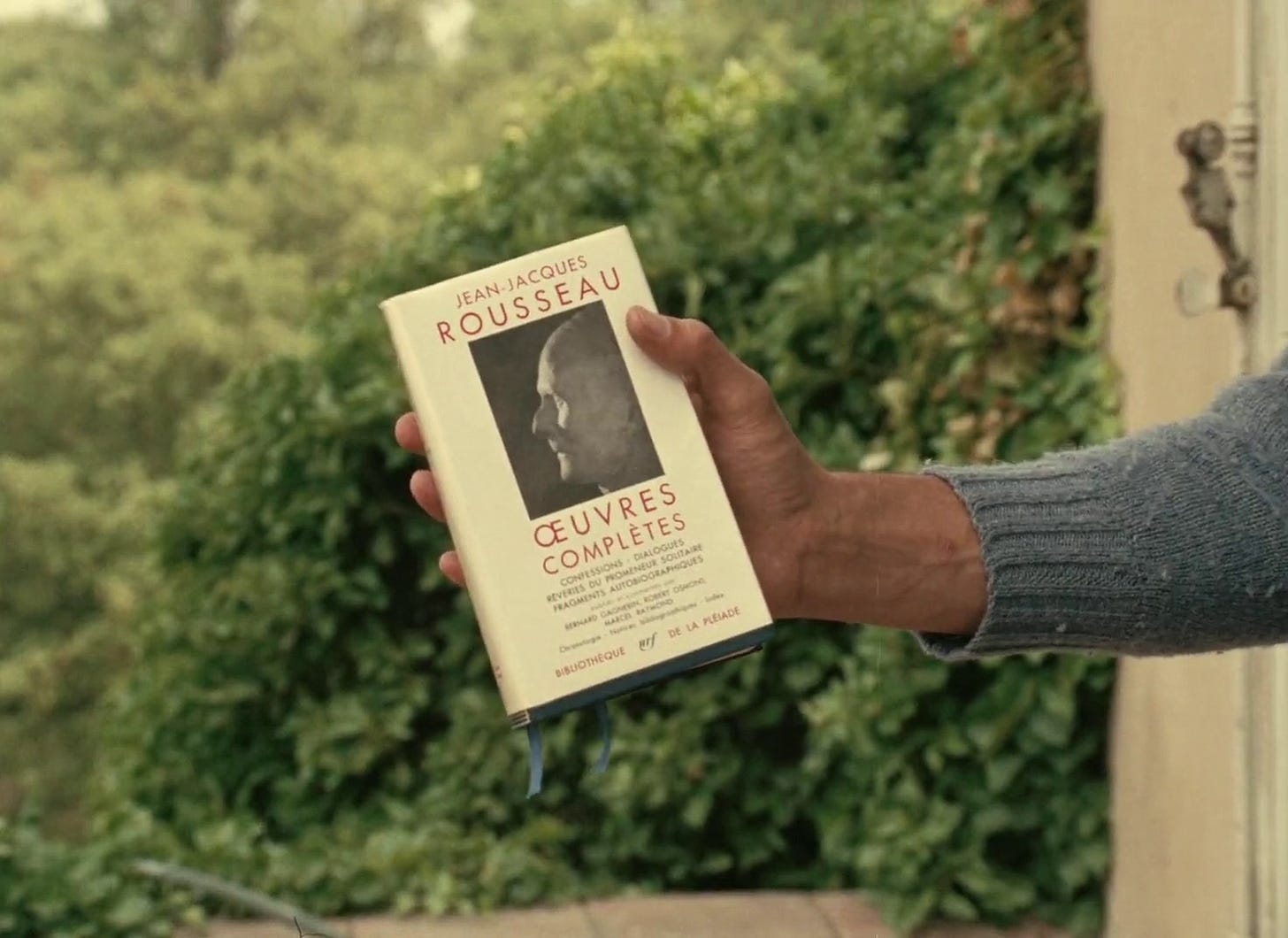

Often shaded from the summer sun, the three companions live life at a languid pace, practising lethargy and slow-motion mind games in that way only the French know how to do. But while the men seem to be restless despite affecting airs of superiority, Haydee lives her life as she wishes. During the day, she rests and reads books. At night, her male friends drive up to the Villa and take her to the beach. By dawn, she returns to sleep. The men, however, decide Haydee is a slut who has sex with her male friends. They both claim not to have sexual desires for her, talking themselves into an undeclared contest to see who will first succumb to being part of Haydee’s collection. This assumes that the young woman is simply there for the taking, like a worn-out piece of antique art, which is by no means the case.

Adrien, in particular, is only at the villa because he refused to travel to London with his girlfriend for no good reason. He confides in us, in his narration, a longing for solitude and a wish to spend his vacation doing nothing, but as the film's narrator, he’s very unreliable. His actions convey the opposite of his musings. When, Sam (Seymour Hertzberg), a wealthy art collector visits the villa to look at an old Chinese vase Adrien is selling, Adrien promptly offers Haydee to the older man out of spite. He disguises this spite by telling himself that he does it for more practical, business reasons. This leads us to form our own conclusions on the kind of person Adrien is.

Éric Rohmer (1920-2010) was the last of his generation to join the French New Wave cinema, but he had a more deliberate narrative style, sidestepping events which conventional directors would have exploited immediately. His Six Moral Tales portrayed rohmerian characters who often acted without thinking of their actions, or acted in contradiction to their ideals. They were never exactly moral, and neither was their alleged morality one the audience necessarily agreed with. This way, Rohmer himself puts his position on morality up for debate.

The third of Eric Rohmer’s Six Moral Tales, the first at feature length, and his first feature filmed in color, “La Collectionneuse” opens with the camera focusing on Haydée in a bikini as she walks in the waves at the edge of the sea. Via the camera we regard her body part by part: Her legs, her thighs, her stomach, her chest, her ears, hands, and throat. It’s subtly brilliant how Rohmer sets her up as an object of desire in a film that serves to indefinitely postpone the realization of any desire both the characters and viewer may feel. One wonders if this scene in some way inspired his 1970 film, Claire’s Knee.

I saw my first Rohmer film, Suzanne’s Career (1963), sometime in late October 2021. Suzanne, not unlike Haydee, finds herself in the middle of attention between two friends. This formed my introduction to the women of Rohmer’s world. They were women more assured in their imperfections than their male counterparts who often overcompensated, and went to extra lengths to get close to the women. As a filmmaker, Éric Rohmer was late to join the French New Wave, but as editor of the influential Cahiers du Cinema, Rohmer was at the vanguard, publishing the film reviews of future directors such as Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Claude Chabrol. When “La Collectioneuse” was released in 1967, Godard, Resnais, Chabrol, Varda and Truffaut were already well-established as auteurs of French Cinema.

Yet, to watch La Collectionneuse, or any Rohmer film for that matter, creates a sense of peaceful contemplation totally distinct from anything his contemporaries made. Here was a filmmaker unafraid to lose his audience’s attention with too much dialogue, or too little action. He invites us to arrive at our own moral judgments. With Nestor Almenderos directing the photography, this film functions as a jumping-off point for the rest of their prestigious film careers. They eventually made nine films together, and Nestor himself went on to win an Oscar award for Best Cinematography in respect of his work on Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven. His exuberant, thoughtful approach fit perfectly with Rohmer’s desire to look at characters and at least, try to understand them.

Eric Rohmer's films often encapsulated much of the emotional inertia and narcissism of youth, especially his Six Moral Tales. The moral tales examined questions of romance, and while there was little or no sex in them, there was often discussion about it. His camera caressed them as they spoke about the possibility of caressing each other. Of course, the focus is on the way human beings play the game of romance, with hesitation, subterfuge and sometimes waywardness. Rohmer constantly returned to this theme with films as full of dialogue as most modern films forbid it. It is here I find my closest connection to anyone as a filmmaker, making Éric Rohmer the most influential teacher on my journey as a student of cinema.

Whether Rohmer films are old-fashioned is an academic point. In my view, he has more in common with Jean Renoir, the old master of French cinema, than either Godard, Truffaut, Jacques Rivette or Chabrol. His point, well-made in La Collectionneuse as in the other Moral Tales, is that the secret dilemmas and machinations of individuals are as important as those of the collective society at large.

0 Comments

Post a Comment